Trump’s Board of Peace: Bold reset or bypass of Palestine?

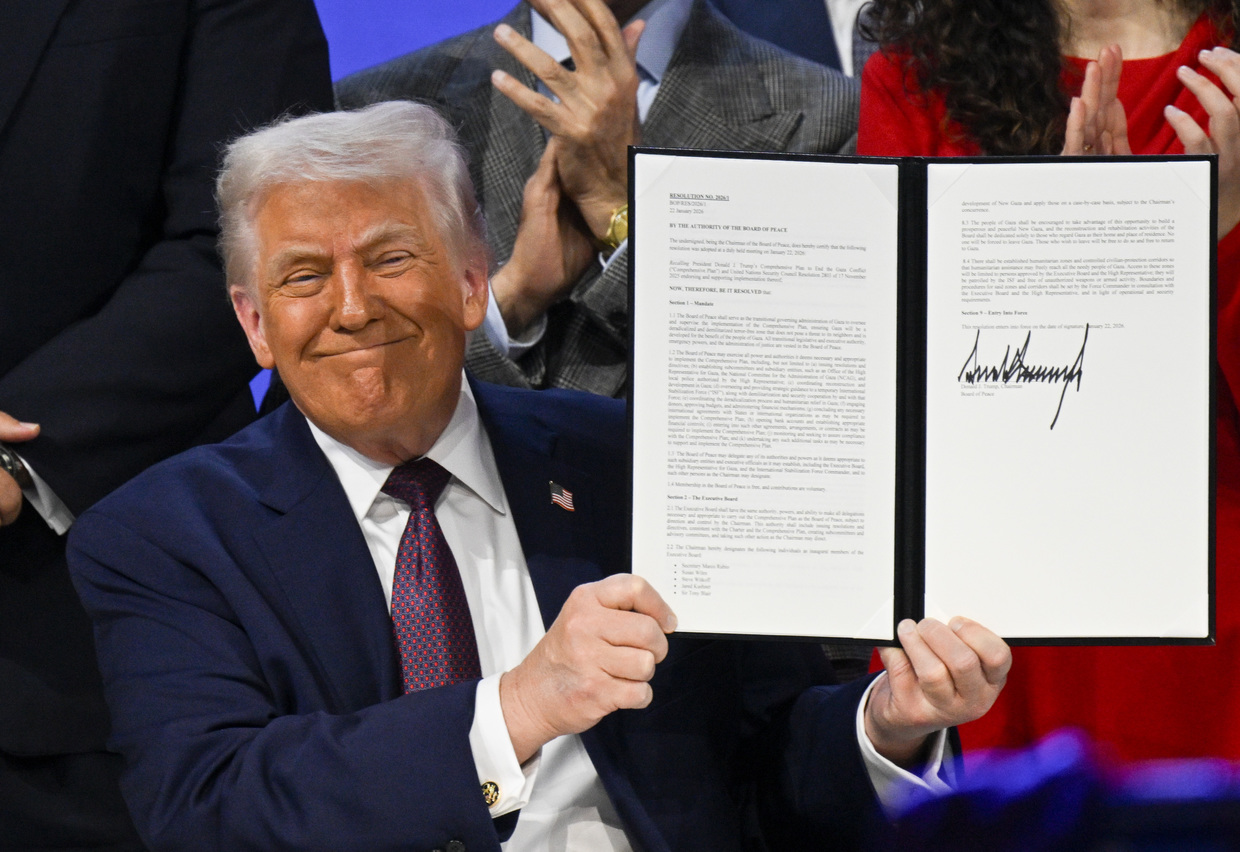

Unveiled with fanfare in Davos, US President Donald Trump’s newly minted Board of Peace (BoP) is being billed as a game-changer for Gaza and the wider Middle East.

Backed by 25 states and armed with a formal legal mandate, the body aims to oversee Gaza’s reconstruction, guarantee Israel’s security, and, ultimately, break the deadlock in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Reactions to the initiative have been sharply divided. Supporters view the Board of Peace as a pragmatic response to exhaustion after years of war, while skeptics question its legitimacy, mandate, and most notably, the absence of Palestinian political representation.

With Israel directly involved and Palestinians sidelined, doubts persist over whether the initiative can deliver peace rather than simply manage a crisis.

To assess the BoP’s prospects and pitfalls, RT spoke with three experts, from Palestine, Saudi Arabia, and Türkiye, asking how the initiative is perceived across the region, how it differs from past US peace efforts, and whether it stands any real chance of reducing violence or reshaping Middle East diplomacy altogether.

RT: How is Trump’s proposed Board of Peace being viewed in your country and the wider region?

Mohammed Najib, a Ramallah-based analyst and journalist: In Palestine, Gaza and the West Bank, the prevailing mood is skepticism, mixed with fatigue and conditional hope. The initiative is widely seen as an external framework that still does not resolve core political questions (sovereignty, governance legitimacy, Israeli withdrawals). Any mechanism tied to ceasefire durability, crossings, aid, and reconstruction can bring immediate relief.

The Gazan people raise doubts about whether the plan will change conditions on the ground, given the ongoing insecurity and hardships despite the ceasefire framework.

In the wider region, reactions are split and transactional. Several key regional states have signaled their willingness to participate (or to explore participation, such as Jordan) in managing a post-war Gaza file and preventing regional spillover, while European powers have shown caution, partly due to governance and mandate ambiguity and partly because the body could undermine established multilateral structures.

The Palestinians believe there are two main obstacles: Israel, which controls the Gaza borders and could obstruct the free entry of reconstruction materials into Gaza, or refuse to withdraw from Gaza; and Hamas, which still has influence over the Gazan people, despite accepting the transfer of authority to the newly formed Palestinian technocratic Administrative Committee, and could apply the Lebanese model, with a civilian government but the real force and power in Hezbollah’s hands.

Actually, the Palestinians in Gaza believe that Israel will not fully withdraw from Gaza and that it is merely maneuvering and buying time.

Khaled Batarfi, a professor at Faisal University: Saudi Arabia sees the initiative through a pragmatic and forward-looking lens. The region has been exhausted by cycles of war in Gaza, and any framework that can support a sustainable ceasefire, reconstruction, and humanitarian access is viewed as a potential platform for stability.

Riyadh’s position is consistent: if a mechanism, whether American-led or multilateral, can reinforce international law, reduce violence, and help deliver an organized post-war environment in Gaza, then it deserves to be explored.

Across the region, governments are cautious but generally hopeful. There is recognition that the Middle East needs new tools and fresh diplomatic formats capable of breaking long-standing deadlocks, provided that they complement, rather than replace, the UN framework.

Gökhan Batu, an expert on Israel and Middle Eastern affairs based in Ankara: Despite economic constraints, Türkiye enters this period with enhanced regional influence, strengthened by defense investments, advanced technology, and an active diplomatic posture. Over the past five years, Ankara has largely secured its objectives in regional contests without provoking major crises, making cooperation with Türkiye increasingly attractive for many actors.

Peace-building and mediation have long been central to Turkish foreign policy, alongside President Erdogan’s critique of the UN Security Council, encapsulated in the phrase “The world is bigger than five.” In this sense, the BoP aligns with long-standing Turkish concerns about the inadequacy of the current global order.

However, Ankara remains cautious. Provisions granting extensive authority to the Chairman and certain decision-making mechanisms diverge from Türkiye’s perspective. Given ongoing uncertainties and the likelihood of revisions, Türkiye is expected to continue observing developments rather than taking a definitive stance.

RT: Does this plan represent a genuine diplomatic effort, or is it symbolic or political in nature?

Najib: It is diplomacy in form, but political signaling in structure; diplomacy explicitly linked to sustaining the Gaza ceasefire and to post-war stabilization and reconstruction discussions, with prominent international figures and states invited to participate.

Political signaling in structure because reporting indicates major uncertainties about the mandate, decision-making processes, and legitimacy, alongside controversial features such as a proposed $1 billion “buy-in” for permanent membership and concerns raised by diplomats and allies that it may rival or bypass the UN system rather than strengthen it.

Even wire coverage notes that the initiative was unveiled with limited operational detail at launch, another reason many observers treat it as partly symbolic until the implementation rules are clear.

Also, the Palestinians believe that some countries joined the Board of Peace not because they are persuaded by it, but to avoid the consequences of angering Trump by rejecting it.

Gaza has now come under US CENTCOM control, so the Palestinians see that they are heading towards a foreign mandate.

Batarfi: From a Saudi perspective, intentions matter less than outcomes. If the Board of Peace contributes to stopping the war, enabling aid, rebuilding Gaza, and creating conditions for a political horizon, then it becomes a practical diplomatic tool.

The structure may carry symbolic or political elements, but what matters to Riyadh is whether the body can deliver tangible results: stability on the ground, accountability, and a more predictable environment for civilians.

In that sense, the plan has the potential to move beyond symbolism, if it operates in partnership with regional actors and in line with the UN-approved Gaza plan.

Batu: The plan reflects a broader shift in US policy under Trump’s second term, where international institutions, especially the UN, are increasingly portrayed as liabilities rather than assets. The US withdrawal of funding from UN bodies and debates within NATO point to a serious challenge to the post–World War II international order and signal a painful transition phase.

Initially framed as a Gaza-focused mechanism, the Board of Peace has rapidly expanded in scope toward the broader Middle East, and potentially beyond. Recent US positions, such as openly discussing the acquisition of Greenland, further undermine the UN system and challenge the authority of the Security Council.

The BoP’s structure suggests an alternative, multi-country model to the UN Security Council, while also functioning as a manifesto of “burden-sharing” and strategic contraction. Its charter implicitly criticizes existing institutions and signals a US willingness to move beyond them. While it is premature to assess whether it could replace the Security Council, its political and symbolic significance should not be underestimated. Membership may bring prestige, but it also entails serious responsibilities, requiring careful assessment by participating states.

RT: How does it differ from previous US-led peace initiatives?

Najib: Past efforts, such as the Roadmap 2003 and Annapolis 2007, were structured around negotiated steps and obligations by the parties, often embedded in established multilateral formats (the Quartet, UN references). The Roadmap was explicitly “performance-based,” with phases and benchmarks.

Crisis governance focus (Gaza administration and reconstruction) vs. final-status resolution: the current Board of Peace is first presented as a mechanism to oversee the durability of the ceasefire and Gaza’s post-war management and reconstruction, with “peace” framed as an outcome of stabilization and investment rather than as a classic final-status negotiation track.

A recurring Trump-era pattern: asymmetry in representation and “deal” framing. The 2020 Trump plan (“Peace to Prosperity”) has been criticized for excluding Palestinians from the unveiling and for being perceived as heavily shaped by Israeli preferences. Analysts note echoes of that dynamic when Palestinians argue that governance arrangements are being designed around them rather than with them.

Batarfi: Three differences stand out. The first one is regional integration: The initiative brings Arab and Islamic states into the operational management of Gaza’s recovery. This contrasts with earlier US efforts, where regional actors played a supporting role rather than a central one.

The second one is the focus on post-war governance: Instead of offering a final-status solution upfront, the Board focuses on stabilizing Gaza, coordinating reconstruction, and managing a transitional phase, areas where practical cooperation is urgently needed.

And, lastly, the concept of multilateralism, not bilateralism: Unlike initiatives centered on Israeli-Palestinian talks alone, this framework incorporates multiple states, donors, and security actors in an organized structure. This wider coalition could make implementation more resilient.

Batu: Starting with the 20-Point Plan, this initiative is among the most clearly defined frameworks since the Oslo process. Unlike past approaches based on vague declarations, it reflects an acknowledgment that such methods have failed to advance peace. However, the process remains heavily dependent on Trump’s insistence on continuity and pressure on Netanyahu.

Historically, the US either tolerated or supported a shift in the balance in Israel’s favor, particularly during Trump’s first term. In contrast, the BoP signals a relatively more balanced approach, shaped by post–October 7 realities that have also affected US interests and regional perceptions.

While multiple actors, including Türkiye, Pakistan, and Qatar, may influence developments in Gaza, the US remains the key actor capable of exerting decisive pressure on Israel, a fact underscored by Netanyahu’s visible discomfort with US leverage.

RT: Given the realities on the ground, how effective can this Board realistically be?

Najib: A realistic ceiling can help manage a fragile ceasefire and coordinate reconstruction-related diplomacy if key enforcement and access issues move in the right direction.

Hard constraints reported on the ground include ongoing incidents, contested lines of control, and Israeli actions that Palestinians and others say contradict ceasefire maps, dynamics that undermine trust and complicate any stabilization mechanism.

So the board’s effectiveness depends less on its “brand” and more on its ability to produce credible security arrangements (deconfliction, rules, monitoring), reliable access and logistics (crossings, aid flows),and enforceable sequencing (withdrawals, governance transition, demilitarization terms).

Batarfi: The Board can be effective if it stays anchored in three principles that Saudi Arabia consistently emphasizes: An immediate and sustained ceasefire leading to reduced violence and the protection of civilians, serious investment in reconstruction and restoring basic services (with transparent and accountable mechanisms), and a coordinated security environment that prevents a power vacuum and avoids any unilateral Israeli control over Gaza.

If these pillars are honored, the Board could help stabilize Gaza, prevent renewed escalation, and create a more coherent environment for future political negotiations.

Batu: As long as Trump maintains his insistence, the initiative will continue in some form. Without US pressure, Israel would not have agreed to a ceasefire or to advancing to the second phase of the 20-Point Plan. Israel’s original aim was to reshape Gaza through territorial confinement and buffer zones, creating a new long-term status quo.

However, broader strategic calculations, including US interests, reinforced Trump’s determination to proceed. For the Board of Peace to succeed, stability in Gaza must be sustained, as Gaza will serve as its primary test case. If stability collapses, the board itself will inevitably fail.

RT: Why are Palestinian representatives not included while Benjamin Netanyahu is? Can it work without the Palestinians?

Najib: Why is Netanyahu included? Well, Israel is a decisive on-the-ground military and political actor in Gaza and the West Bank, and Israeli consent is required for any security, crossing, or reconstruction pathway. This gives Netanyahu structural leverage in any externally designed mechanism.

As for the Palestinians: reporting across the board has emphasized technocratic Palestinian administration and external oversight structures rather than formal political representation at the top table, an approach intended to avoid internal Palestinian fragmentation (Palestinian Authority vs Hamas vs factions), but it also produces a legitimacy deficit.

The Palestinians are concerned that there is no Palestinian representative on the Board of Peace, while there is an Israeli businessman, Yakir Gabay, and the Israeli prime minister, Benjamin Netanyahu, and the PA is excluded.

The PA had asked a European Country to join the CMCC in Kiryat Gat, as a senior PA security official confirmed on Thursday.

Batarfi: Saudi Arabia’s position is clear: no peace initiative can succeed without meaningful Palestinian participation. Their absence at this stage reflects political complexities, internal divisions, and sensitivities around representation, but it cannot be permanent.

For the board to function credibly, Palestinian voices must become integral to its decisions, whether through a reformed Palestinian Authority, a technocratic administration, or a unified national mandate supported by elections.

Netanyahu’s presence is explained by the reality that Israel is a direct actor in the conflict. But long-term success depends on giving Palestinians equal representation in shaping Gaza’s future.

Batu: Hamas has already agreed to relinquish control of Gaza once conditions are met, yet both Hamas and Islamic Jihad view the BoP as a mandate-based arrangement with serious implementation risks. Palestinians, particularly since the return of the hostages, have been pushed into an almost entirely passive role in negotiations.

This dynamic mirrors earlier criticisms of UN Security Council Resolution 2803, which framed Palestinian self-determination and statehood as conditional outcomes rather than established rights, while avoiding reference to key resolutions such as 242 and 338. Israel has also made clear its refusal to work with either Gaza-based groups or the Palestinian Authority.

In practical terms, the collapse of the process would likely mean a return to war, despite Gaza’s unresolved humanitarian catastrophe. Excluding Palestinians thus carries significant political and moral costs.

RT: What message does Palestinian exclusion send to the region and to Palestinians themselves?

Najib: To many Palestinians, exclusion signals that their future is being negotiated as a security management file, not as a political question of self-determination, and that “governance” is being substituted for “representation.”

Regionally, it reinforces a familiar pattern; Arab and Muslim states (Qatar, Egypt, Jordan, Türkiye) may engage for containment and humanitarian necessity, but the political credibility of the project is undermined if Palestinians are perceived as absent from the decision-making, especially when the initiative is marketed as “peace.”

Batarfi: The absence of Palestinians risks sending the wrong message - that their role is secondary in a conflict that directly affects their people. Saudi Arabia, however, has been very consistent: Palestinians must be partners, not spectators.

Riyadh stresses in every forum, from the UN to bilateral channels, that no arrangement is legitimate unless it reflects Palestinian rights, aspirations, and political agency.

The optimistic reading is that this is an initial configuration, not the final structure. The true test of the board will be how quickly and seriously it brings Palestinians into the core decision-making processes.

Batu: As noted earlier, Palestinian exclusion reinforces their passive position in the process. While not justifiable, sidelining Palestinians may be seen as a way to keep Israel engaged. In this context, the involvement of Türkiye and Qatar may serve as partial compensation for the lack of direct Palestinian representation.

RT: Is there a realistic pathway for this effort to reduce violence or even end the conflict? What conditions must change for lasting peace?

Najib: Reducing violence – there is a plausible pathway if the board or any mechanism can lock in sustained ceasefire compliance, predictable humanitarian access, economic stabilization, and credible security governance that reduce incentives for renewed fighting.

Ending the conflict is far harder, as lasting peace would require at least four conditions: legitimate Palestinian political representation in any binding process (not only in a technocratic administration); a defined end-state horizon (rights, sovereignty, borders, security arrangements, whatever the agreed model); enforceability – monitoring and consequences for breaches, particularly on control lines, access, and the protection of civilians; and regional and international alignment on financing, governance and security sequencing to ensure that reconstruction is not divorced from political legitimacy.

In short, the Board of Peace can potentially freeze escalation and manage recovery, but without Palestinian political inclusion and an enforceable political horizon, it is more likely to operate as crisis management than as conflict resolution.

Batarfi: It can succeed, if the Board is used as a platform for coordinated, sustained de-escalation. Three conditions are essential: First, a stable ceasefire with enforceable guarantees. This is the immediate priority and the one area where a multilateral body can make a rapid impact.

Second, a credible political horizon: The region overwhelmingly supports a two-state solution. Without a viable pathway toward Palestinian statehood, any temporary calm will remain fragile. Saudi Arabia sees political progress as indispensable.

And third, regional and international alignment: if the US, key Arab states, and the broader international community work together through this Board, rather than competing, then reconstruction, security assistance, and institution-building become achievable.

Under these conditions, the Board could serve as a bridge: reducing suffering now, while laying the groundwork for a durable and just peace.

In a nutshell, Saudi Arabia supports any serious effort that brings the guns to silence, opens a path for rebuilding Gaza, empowers Palestinians, and anchors the region in a stable, rules-based order. The Board of Peace can contribute to this goal if it remains inclusive, credible, and aligned with international law.

Batu: Ending the conflict is unrealistic under current conditions, but violence can be reduced as long as Trump succeeds in restraining Israel. In the short term, risks remain high, particularly with Israel heading into elections.

Lasting peace would require the addressing of core structural demands, including borders and statehood. A return to the 1967 borders is highly unlikely, meaning the Board of Peace can at best manage and contain the crisis rather than resolve it. Sustainable peace will require long-term groundwork, not only short-term initiatives.